How often do you hear the acronym AOP? Aspect-oriented programming - aspects are quite a buzzword in the world of software development these days. I gave AOP a quick spin using the Spring framework in Java. According to the Spring framework reference documentation of AOP (http://static.springsource.org/spring/docs/2.5.x/reference/aop.html), "Aspects enable the modularization of concerns such as transaction management that cut across multiple types and objects." I'll show you just how easy implementing AOP can be by presenting a very minimalist example Spring-based Java application. By the end of this blog post, if you read it carefully, you should have a clear idea how you could benefit from AOP, what are the different ways of implementing aspects in your applications and, no doubts, you will feel a certain hype about this. You'll probably want to chuck some AOP into your next piece of development just because it's "so cool" :-)

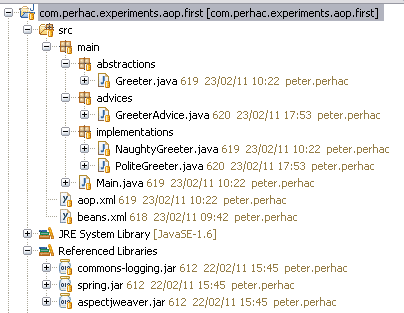

Note there are only three referenced libraries (jars) - spring, it's commons-logging dependency, and aspectjweaver.

The interface above is as simple as it gets - one method, no parameters, no return value, so we focus on demystifying AOP. This is the only interface in our tiny system. We have two different implementations of this interface, as follow:

...what a nice chap. We have also another implementation of a Greeter:

Below comes the Main class, with the entry point - public static void main method.

What's missing is the Spring XML wiring, as I chose to demonstrate how you could implement cross-cutting aspects of your application with the Spring framework, without touching your existing code. All the magic will be performed by Spring and we'll orchestrate the whole symphony from XML. There are other alternatives and many find those much more convenient. However I just wanted to present a simple example and we can discuss the alternatives in later sections of this blog entry.

I decided to separate the AOP-related mark-up into an XML file of its own, so we'll have two XMLs instead of just one, but that's only to show you how you can easily manage your spring contexts without ending up maintaining a huge pile of convoluted mark-up. The basic application context is in this file, note that the first element inside the beans element is an "import", that's how we can link more Spring context files together.

As you can see, half of the mark-up is boilerplate XML stuff and fluff. We define a polite greeter bean and a naughty greeter bean, then we'll declare that the main bean will need these two above-mentioned beans injected into its greeters property, which is an array of Greeter, so we define it as a list element, Spring can do the magic of dependency injection.

Surprisingly, the aop.xml file does not contain tons of mark-up. We simply stated that there is an advice for the application lurking somewhere in our code base (the last bits of Java code that will be listed in this post). And we also indicated that there exists an advisor bean that we would like the Spring container take into consideration. This single bean is probably the most interesting, as it contains not only a reference to the advice being applied to our application execution (the "what" and the "when" of the aspect we're implementing), but also the places "where" we would like the Spring container to interfere with our application's execution, intercept the access to particular join points and enable us to perform the cross-cutting trickery we have in mind :-)

There is also one other exciting line of mark-up, which is post processor bean that will enable auto-proxying of our target classes, but more on that a bit further down this post. I aim to demystify the scary terms, and so demystify I will! But hang on...

Wow, that wasn't that huge, was it? I mean, it really isn't that very mind-boggling piece of code. We basically just implement the what and the when of an aspect. As to "what", the code inside the individual methods is the "what". It's the extra bits of logic to be tacked onto your application's logic in a cross-cutting manner. The "when" of this aspect is the actual methods you used in order to implement the advice. You could have used a before / after / on exception / after (finally) / or an "around advice". In our particular example, we used only the before (something happens in our application) and the after. In a different setup you could perhaps be interested in reacting to exceptions thrown.

Say, maybe you would like to log every exception thrown within your system (or just a particular kind of exception within a particular layer of your system) in a special error log. A bit of code into the right place in your Advice class, and a tiny bit of XML mark-up is all you need to do. Can you feel the power of AOP yet? And how relatively simple that could be. The extra complexity added, once you have overcome the initial shock and swallowed all the definitions and the concepts introduced by using Spring as application framework, you'll be able to do great things by a wave of the magic wand (couple of lines of XML and Java code).

Let us have a look at the advice implemented above: a message is printed to the console before a method is invoked, and a message is printed after the method returns. So we now know when and what is going to happen, we still don't know where (and "how", which is mysterious auto-proxying mechanism, courtesy of the Spring framework). Back to the aop.xml Spring context file - in it you will find the definition of the advisor bean.

The primitive pointcut used in this case - execution - "Picks out each method execution join point whose signature matches MethodPattern." (http://www.eclipse.org/aspectj/doc/released/progguide/semantics-pointcuts.html). The MethodPattern we have provided in our example case is quite simple, of course: a method called "greet" of any visibility, in any package, taking any number and kind of arguments will cause Spring to apply the advice accordingly (before it's invoked or after or both or on exception). There's a lot more to the method patterns in the AspectJ pointcut expression syntax, so feel free to rummage the website to find out more details.

We are using the org.springframework.aop.framework.autoproxy.DefaultAdvisorAutoProxyCreator BeanPostProcessor that will, according to the documentation, "creates AOP proxies based on all candidate Advisors in the current BeanFactory". A long story short, it will figure out which objects need to be proxied (where to sneak in an extra thin layer of indirection) in order for our good-hearted advice to be applied.

I believe a picture says a thousand words:

Every method call matching the AspectJ pointcut expression will be intercepted by a proxy, forwarded to you advice, then executed, then pass back through your advice and then returns.

So... if you cared to scroll all the way back up to the code listing for our Main class, you could see that the expected output of running the application would be two lines: one, a greeting from the polite greeter, and the other an abrupt message from the naughty greeter. However, if you copy-pasted code carefully, when you run the application, the following output is produced:

That's amazing! Our code was kindly advised to pre-output a short description of what's about to happen before each call to the greet() method on a greeter, and also to make it quite explicit that a greeter is done greeting us, by printing "DONE". That is the aspect of our application. One could then present this wonderful piece of software to a client a say: "One of the awesome aspects of our system is that the user is always notified of everything that is about to happen and also is told right-away when an action has finished executing."

Realistically, this aspect is quite useless, just like the application itself, but consider this: You have developed a complete application and you can tell your client "One important aspect of the system is that every operation on the service layer is atomic - wrapped in a transaction. It either succeeds or fails as a unit and whenever any failure is encountered, an entry is made into the error log and the transaction is rolled back."

By defining your pointcut carefully, you could then advise this transactional behaviour to all of the public service methods and stay cool.

Happy coding!

The sample application

The sample application is, as I mentioned earlier, minimalist and completely fictitious. I removed all extra stuff from the application on purpose, just to make sure it does not contain more than is absolutely necessary.Note there are only three referenced libraries (jars) - spring, it's commons-logging dependency, and aspectjweaver.

package main.abstractions;

public interface Greeter {

void greet();

}The interface above is as simple as it gets - one method, no parameters, no return value, so we focus on demystifying AOP. This is the only interface in our tiny system. We have two different implementations of this interface, as follow:

package main.implementations;

import main.abstractions.Greeter;

public class PoliteGreeter implements Greeter {

@Override

public void greet() {

System.out.println("Good afternoon!");

}

}...what a nice chap. We have also another implementation of a Greeter:

package main.implementations;

import main.abstractions.Greeter;

public class NaughtyGreeter implements Greeter {

@Override

public void greet() {

System.out.println("Leave me alone!");

}

}Below comes the Main class, with the entry point - public static void main method.

package main;

import main.abstractions.Greeter;

import org.springframework.context.ApplicationContext;

import org.springframework.context.support.ClassPathXmlApplicationContext;

public class Main {

private Greeter[] greeters;

public void setGreeters(Greeter[] greeters) {

this.greeters = greeters;

}

private void run() {

for (Greeter greeter : greeters) {

greeter.greet();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

ApplicationContext context = new ClassPathXmlApplicationContext("beans.xml");

((Main) context.getBean("main")).run();

}

}What's missing is the Spring XML wiring, as I chose to demonstrate how you could implement cross-cutting aspects of your application with the Spring framework, without touching your existing code. All the magic will be performed by Spring and we'll orchestrate the whole symphony from XML. There are other alternatives and many find those much more convenient. However I just wanted to present a simple example and we can discuss the alternatives in later sections of this blog entry.

I decided to separate the AOP-related mark-up into an XML file of its own, so we'll have two XMLs instead of just one, but that's only to show you how you can easily manage your spring contexts without ending up maintaining a huge pile of convoluted mark-up. The basic application context is in this file, note that the first element inside the beans element is an "import", that's how we can link more Spring context files together.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:aop="http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop" xmlns:context="http://www.springframework.org/schema/context"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans-2.5.xsd

http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop

http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop/spring-aop-2.5.xsd

http://www.springframework.org/schema/context

http://www.springframework.org/schema/context/spring-context-2.5.xsd">

<import resource="aop.xml" />

<bean id="politeGreeter" class="main.implementations.PoliteGreeter" />

<bean id="naughtyGreeter" class="main.implementations.NaughtyGreeter" />

<bean id="main" class="main.Main">

<property name="greeters">

<list>

<ref bean="politeGreeter" />

<ref bean="naughtyGreeter" />

</list>

</property>

</bean>

</beans>As you can see, half of the mark-up is boilerplate XML stuff and fluff. We define a polite greeter bean and a naughty greeter bean, then we'll declare that the main bean will need these two above-mentioned beans injected into its greeters property, which is an array of Greeter, so we define it as a list element, Spring can do the magic of dependency injection.

The Advisor enters the scene

So far no huge surprises. A ridiculously simple application. Now, the really interesting bits come in the next piece of XML, and in the Java code fragment in the next section.<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:aop="http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop" xmlns:context="http://www.springframework.org/schema/context"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans-2.5.xsd

http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop

http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop/spring-aop-2.5.xsd

http://www.springframework.org/schema/context

http://www.springframework.org/schema/context/spring-context-2.5.xsd">

<!-- no id - will never be referred to directly. The Spring container will recognise it as a BeanPostProcessor -->

<bean class="org.springframework.aop.framework.autoproxy.DefaultAdvisorAutoProxyCreator" />

<bean id="greeterAdvice" class="main.advices.GreeterAdvice" />

<bean id="greeterAdvisor" class="org.springframework.aop.aspectj.AspectJExpressionPointcutAdvisor">

<property name="advice" ref="greeterAdvice"></property>

<property name="expression" value="execution(* *.greet(..))" />

</bean>

</beans>Surprisingly, the aop.xml file does not contain tons of mark-up. We simply stated that there is an advice for the application lurking somewhere in our code base (the last bits of Java code that will be listed in this post). And we also indicated that there exists an advisor bean that we would like the Spring container take into consideration. This single bean is probably the most interesting, as it contains not only a reference to the advice being applied to our application execution (the "what" and the "when" of the aspect we're implementing), but also the places "where" we would like the Spring container to interfere with our application's execution, intercept the access to particular join points and enable us to perform the cross-cutting trickery we have in mind :-)

There is also one other exciting line of mark-up, which is post processor bean that will enable auto-proxying of our target classes, but more on that a bit further down this post. I aim to demystify the scary terms, and so demystify I will! But hang on...

Glossary of terms in AOP

Now, I have thrown quite a bit of jargon into the mix, which is not what I like to do, but what is important to do in this case. There are certain terms in the area of AOP that you will need to familiarise yourself with, so next comes a brief glossary:Aspect

The merger of advice and pointcuts. All information about where, when and what job is to be done.

Advice

The job of an aspect. Defines the what and when of an aspect.

Pointcut

Pointcuts help narrow down the joinpoints advised by an aspect. Define the where of an aspect.

Joinpoint

A point in the execution of an application where an aspect can be plugged in. All the opportunities for advice to be applied.

Introduction

Allows us to add new methods and attributes to existing classes without having to change them.

Target

Object being advised.

Proxy

The object created after applying advice to the target object. To the client making use of the target object the proxy looks the same.

Weaving

Process of applying aspects to a target object to create a new, proxied object.

An AOP Advice demystified

Here is the last piece of code I mentioned before on several occasions:package main.advices;

import java.lang.reflect.Method;

import org.springframework.aop.AfterReturningAdvice;

import org.springframework.aop.MethodBeforeAdvice;

public class GreeterAdvice implements MethodBeforeAdvice, AfterReturningAdvice {

@Override

public void before(Method method, Object[] args, Object target) throws Throwable {

System.out.printf("%s is about to greet you: \n>>>", target.getClass().getSimpleName());

}

@Override

public void afterReturning(Object returnValue, Method method, Object[] args, Object target) throws Throwable {

System.out.println("DONE");

}

}Wow, that wasn't that huge, was it? I mean, it really isn't that very mind-boggling piece of code. We basically just implement the what and the when of an aspect. As to "what", the code inside the individual methods is the "what". It's the extra bits of logic to be tacked onto your application's logic in a cross-cutting manner. The "when" of this aspect is the actual methods you used in order to implement the advice. You could have used a before / after / on exception / after (finally) / or an "around advice". In our particular example, we used only the before (something happens in our application) and the after. In a different setup you could perhaps be interested in reacting to exceptions thrown.

Say, maybe you would like to log every exception thrown within your system (or just a particular kind of exception within a particular layer of your system) in a special error log. A bit of code into the right place in your Advice class, and a tiny bit of XML mark-up is all you need to do. Can you feel the power of AOP yet? And how relatively simple that could be. The extra complexity added, once you have overcome the initial shock and swallowed all the definitions and the concepts introduced by using Spring as application framework, you'll be able to do great things by a wave of the magic wand (couple of lines of XML and Java code).

Let us have a look at the advice implemented above: a message is printed to the console before a method is invoked, and a message is printed after the method returns. So we now know when and what is going to happen, we still don't know where (and "how", which is mysterious auto-proxying mechanism, courtesy of the Spring framework). Back to the aop.xml Spring context file - in it you will find the definition of the advisor bean.

Defining the pointcut

It defines which Advice is to be used, and also where to apply this advice to our application. Since we (wisely) chose the advisor bean to be of type org.springframework.aop.aspectj.AspectJExpressionPointcutAdvisor, we'll be using an AspectJ expression to define the pointcut. The expression injected into the advisor bean is this: execution(* *.greet(..))The primitive pointcut used in this case - execution - "Picks out each method execution join point whose signature matches MethodPattern." (http://www.eclipse.org/aspectj/doc/released/progguide/semantics-pointcuts.html). The MethodPattern we have provided in our example case is quite simple, of course: a method called "greet" of any visibility, in any package, taking any number and kind of arguments will cause Spring to apply the advice accordingly (before it's invoked or after or both or on exception). There's a lot more to the method patterns in the AspectJ pointcut expression syntax, so feel free to rummage the website to find out more details.

How does it work? Proxies

Given this complete definition of the Advisor bean, we are now so very close to demystifying the whole lot. The one unanswered question remaining is the "how". By sheer black magic, I tells ya. :-) You can either add a pretty bit of confusing mark-up to your XML application contexts or you can use the Spring's auto-proxying capabilities. Dynamic proxies will be generated for your application. These will wrap implement the interface of our greeters, so will look like the real thing, but of course these will be fakes that will apply the advice as and when we the advice specifies.We are using the org.springframework.aop.framework.autoproxy.DefaultAdvisorAutoProxyCreator BeanPostProcessor that will, according to the documentation, "creates AOP proxies based on all candidate Advisors in the current BeanFactory". A long story short, it will figure out which objects need to be proxied (where to sneak in an extra thin layer of indirection) in order for our good-hearted advice to be applied.

I believe a picture says a thousand words:

Every method call matching the AspectJ pointcut expression will be intercepted by a proxy, forwarded to you advice, then executed, then pass back through your advice and then returns.

So... if you cared to scroll all the way back up to the code listing for our Main class, you could see that the expected output of running the application would be two lines: one, a greeting from the polite greeter, and the other an abrupt message from the naughty greeter. However, if you copy-pasted code carefully, when you run the application, the following output is produced:

PoliteGreeter is about to greet you:

>>>Good afternoon!

DONE

NaughtyGreeter is about to greet you:

>>>Leave me alone!

DONE

>>>Good afternoon!

DONE

NaughtyGreeter is about to greet you:

>>>Leave me alone!

DONE

That's amazing! Our code was kindly advised to pre-output a short description of what's about to happen before each call to the greet() method on a greeter, and also to make it quite explicit that a greeter is done greeting us, by printing "DONE". That is the aspect of our application. One could then present this wonderful piece of software to a client a say: "One of the awesome aspects of our system is that the user is always notified of everything that is about to happen and also is told right-away when an action has finished executing."

Realistically, this aspect is quite useless, just like the application itself, but consider this: You have developed a complete application and you can tell your client "One important aspect of the system is that every operation on the service layer is atomic - wrapped in a transaction. It either succeeds or fails as a unit and whenever any failure is encountered, an entry is made into the error log and the transaction is rolled back."

Uses and benefits of AOP

It is a good idea to wrap your service methods in transactions. You will often want your operations to behave transactionally and fail with grace. Instead of sowing transaction-related code into every corner of your service layer, why not implement transactionality as an aspect, a cross-cutting concern? Get rid of all the "transaction = TransactionManager.beginTransaction(); try { doA(); doB(); ... transaction.commit();} catch (Exception) {logger.log(...); transaction.rollback();} " and keep your service methods rather nice and neat and organized, with focus on "what" the service does, not a myriad other aspects of how it's supposed to be done. You can implement the transactional aspect in separation from that - on top of that - AOP-style, and it's not that complicated. Just implement an "around advice" to start a transaction before a method is invoked, and to handle unhandled exceptions thrown and roll back / commit the transaction as necessary.By defining your pointcut carefully, you could then advise this transactional behaviour to all of the public service methods and stay cool.

Other ways of doing AOP

There's, of course, a variety of ways one could go about implementing AOP. In the recent years, annotations have become quite a useful feature in Java. You can quite successfully avoid having all that XML in your project and use annotations to define your aspects (advices, pointcuts, etc) but I chose to provide you with a highly flexible approach, as you could use XML to wire aspects into your application without touching the existing code base. You don't have to add as much as a single annotation to your classes, doing it the way I have demonstrated above. However, I hear that doing AOP with annotations is sweet and much more convenient - so don't hesitate and give it a go! How hard can it be? Now that you already know almost all about it :-) (far from it, but I don't mean to discourage you).Happy coding!